Kirby Edmonds (1951–2020)

Kirby was born on August 17, 1951 in Huntsville, Texas. As a youth he was educated in Glastonbury, Connecticut; Nairobi, Kenya; and Beirut, Lebanon. He held two degrees from Cornell University, a B.A. in History and an M.P.A. with a major in community and rural development.

HRE USA was only one of Kirby’s lifelong efforts toward social justice. As his obituary in the Ithaca Journal says, “Kirby was a mighty river that flowed through our community and far beyond, watering the positive seeds of possibility.” He was currently the Program Coordinator and a Senior Fellow with the Dorothy Cotton Institute (DCI) and the Cradle to Career Initiative, yet the scope of his work reached well beyond these roles. As his obituary described:

“Everywhere that people of good will united to tackle problems or cultivate opportunities, Kirby was quickly pulled into the center. He took on many roles– contributor, connector, or designated leader, but always encouraged folks to plan actions that would get more power and resources into the people’s hands. Soft spoken and kind, Kirby was skilled in the art of posing incisive questions, ever asking folks to consider who else should be at the table. He had a keen understanding of power and the courage never to shy away from issues of violence, racism, poverty, hunger, and intergroup conflict.“

Read more and learn about the HRE USA Kirby Edmonds Fellowship

Mariana Ferriera (1959- 2025)

Human rights education lost a leading light in the passing of Mariana Ferriera in July of this year. The recipient of the 2017 O’Brien Award, she leaves behind a legacy of intellectual breadth and a profound commitment to justice and human rights education. One of her mantras was, “If you don’t know your rights, you don’t have any!”

Born in 1959 in São Paulo, Brazil, Mariana’s journey as an engaged scholar and activist began early. At the age of 19, at the height of the Brazilian military dictatorship, she taught mathematics at a Xavante Indigenous village in the Brazilian Cerrado, an act of defiance against an oppressive regime that considerable courage and shaped her intellectual work at the intersection of Indigenous knowledge, ethnomathematics, medical anthropology, and human rights.

Dr. Ferreira earned her Ph.D. in 1996 in the prestigious Medical Anthropology joint program at the Universities of California Berkeley and San Francisco, focusing on Indigenous health. She was a professor at San Francisco State University, teaching interdisciplinary courses, such as Human Rights Education for Future Educators, Social Science and Medicine, and Performance and Pedagogy of the Oppressed, which were transformative experiences for students, combining theoretical perspectives, activism, active engagement, critical pedagogy, and community engagement. For over a decade she was the main organizer of San Francisco State’s annual Human Rights Summit. She also guided students in creating public murals across the Bay Area, using art as a tool for learning, healing, and resisting oppression.

Professor Ferreira was a prolific scholar, who wrote more than a hundred articles and plays. Her scholarship blended serious academic rigor with community collaboration. Her research focused on participatory methods, especially among Indigenous peoples. She was committed to valuing non-traditional ways of knowing, especially Indigenous ones. In addition to her scholarly work, she developed health curricula with Bay Area clinics, including the Mission Neighborhood Health Center, reaching underserved patients through culturally sensitive education.

We will remember Mariana not only for her groundbreaking research and brilliance, but also for her warmth and unwavering commitment to marginalized peoples. Her voice will continue to echo through her students, her scholarship, and the communities she helped. She is survived by her husband, Nathan, son Mairum, daughter Djuni, son Pedro, daughter Amanda, and five grandchildren, Naia, Lua, Yali, Andre, and Thomas.

Shulamith Koenig (1930–2021)

In late 2021, human rights education lost one of its earliest and most passionate advocates with the passing of Shulamith Koenig, whom some have called “The Mother of Human Rights Education ” or human rights learning, as she preferred. When she founded the People’s Movement for HRE (PDHRE) in 1988, no other organization in the world had made HRE its sole purpose and no other activist had envisioned its transformative power. Indeed, she was a rebel and a visionary, seeking what she called a “human rights revolution.”

Shula was the driving force behind a campaign advocating for worldwide human rights education that sparked the United Nations (U.N.) Decade for Human Rights Education (1995-2004). As Executive Director of PDHRE, she conducted consultations and workshops with educators and community leaders in more than 60 countries. Under her leadership,

PDHRE established “human rights cities”on every continent. In 2003, the U.N. recognized her work with its prize in the Field of Human Rights.

Born in Israel in 1930, Shula Koenig was an industrial engineer and fierce defender of the human rights of Palestinians, activism that led to her immigration to the United States in the 1960s. She grew that passion for social justice to a global vision of human rights as a way of life for all people. She was an inspiration and mentor to many. As activist Loretta Ross said of her, “She was not perfect, but she was perfectly Shula, a sculptress, artist, mentor, and the grandmother I wish I’d had.” As she said many times in many different ways: “It is not enough to have human rights; it is essential that everyone owns them and are guided in their daily lives by the holistic human rights framework, enabling women and men to participate as equals in the decision-making process towards meaningful, sustainable economic and social transformation. There is no other option.”

In memoriam written by Nancy Flowers in the International Journal of Human Rights Education

J. Paul Martin (1936–2024)

Born in England in 1936, as a young man Paul Martin served as an officer in the British Army and took vows with the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate (OMI). He was educated at the International Roman Scholasticate, where he attended the Angelicum, now called the Pontifical University of St. Thomas Aquinas, earning Licentiates in Philosophy and Theology. Following his ordination to the priesthood in 1964, he was assigned to the new University of Botswana, Lesotho, and Swaziland.

Martin saw human rights education as a transformative essential for all social change, a vision he extended beyond the university. In 1989 he initiated the Human Rights Advocates Program, which brings human rights defenders from the Global South to study at Columbia and make contacts needed to support their work at home. Now in its 35th year, the program has 350 global alumni doing human rights work all around the world. Throughout his years at the Institute, Paul himself traveled extensively in the Global South, helping to establish programs in human rights education in Ghana, Burkina Faso, Uganda, Brazil, Liberia, Haiti, and Ecuador and elsewhere.

In what was perhaps his final publication, “Evaluating the Past and Charting the Future of Human Rights Education,” Martin continues his life-long approach to HRE: both practical and visionary, both local and universal, and always humanistic. He emphasizes the critical need for research in HRE and asks “If more HRE research is needed, what is needed and who should do it?” His response is a challenge for all engaged in HRE, especially teacher-training institutions, to integrate “both the substantive and the pedagogical dimensions into their teaching and research.” For the future he calls for “an international institutional network of actors and researchers.” He would, no doubt, be gratified to know that just such an organization was established last year, the International Association for Human Rights Education (IAHRE).

Excerpts from Nancy Flower’s HRE USA memorial

Edward O’Brien (1945-2015)

Ed came indirectly to human rights through his commitment to law-related education. Although a student at Georgetown Law School and an active opponent of the Vietnam War, Ed recalled that he “still didn’t know the term ‘human rights’” though that is what opposition to the war was all about.” His teaching of public interest courses led him in 1972 to co-found the first Street Law program at Georgetown, where law students went into inner-city DC public schools to teach criminal, consumer, torts, family, housing and constitutional law. He was awarded a Robert F. Kennedy Fellowship, from the RFK Centre for Justice & Human Rights, which helped launch Street Law, Inc. in 1975 by subsidizing Ed’s first year of paid Street Law employment. With Lee Arbetman he published Street Law, a high school textbook now in its ninth edition, having sold over two million copies. Street Law developed a unique model of clinical education in law schools, supporting law students delivering interactive law-related education in secondary school and in other settings, such as prisons and homeless shelters, where access to this kind of information might be limited. The so-called “street law model” is now in practice in law schools throughout the world. However, as Ed has acknowledged, in the early days of Street Law, “We taught human rights, but we still didn’t use the words.”

After his retirement as Executive Director of Street Law, Ed continued to be engaged in many educational and civic activities. He was a founding member of Human Rights Educators USA and served on its Steering Committee until his death. Ed was a strategic, passionate, human rights learner and educator, who dedicated his life to empower youth and adults to practice the core principles of equality, non-discrimination, and justice for all.

Those who had the privilege to know Ed as a colleague, friend, and mentor treasured his professional talents and his personal warmth, generosity, and integrity. As Shulamith Koenig, founder of the People’s Decade for Human Rights Education, observed, Ed was “an original thinker, always looking for new ways and reforms.” He was an inspiration to many, both for his genuine kindness and fairness and his vision and commitment to social justice.

Excerpts from Nancy Flowers & Kristi Rudelius-Palmer’’s HRE USA memorial

Betty Reardon (1929–2023)

Human rights and peace education recently lost one of its earliest and most influential champions, Betty Reardon. Perhaps best known as a founder of the field of peace education, she regarded “Human rights education [to be] as fundamental and constitutive to peace education as human rights are to peace.” Her book Educating for Human Dignity: Learning about Rights and Responsibilities (University of Pennsylvania, 1995) was one of the first resources offering both guidance and materials for teaching human rights in schools.

Dr. Reardon held prominent roles in the establishment of key institutions in the field of peace studies, including founding the Peace Education Center and Program at Teachers College, Columbia University and the International Institute on Peace Education. She was also an accomplished scholar with numerous publications not only on peace education, but also on the intersection of peace with human rights and gender.

Betty Reardon believed in education as the key to a just and peaceful world. A beloved teacher, she inspired a generation of educators and activists. She herself never stopped learning, continuing to research, write, and teach well into her last decade.

In memoriam written by Nancy Flowers in the International Journal of Human Rights Education

David Weissbrodt (1944–2021)

David was a networker and diplomat extraordinaire. He modeled how determination and dedication can change the world through drafting human rights declarations, principles, and amicus briefs to scholarship, teaching, and collective action. David breathed life into human rights dreams and careers, always providing guidance on how to navigate often politically turbulent and dangerous waters. He built institutions, such as the Advocates for Human Rights, the Center for Victims of Torture, and the International Human Rights Internship Program. In 1988, David founded the University of Minnesota Human Rights Center and later launched the world’s largest university online Human Rights Library. Through the Center, he facilitated and funded more than 700 student internships, mentored hundreds of global Fulbright Humphrey Fellows, visiting scholars, and students as well as advised on the establishment of the national human rights education clearinghouse (a vital function now assumed by Human Rights Educators USA).

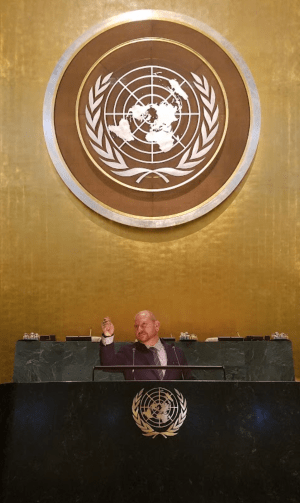

David became Regents Professor at the University of Minnesota, the first from the Law School to be so honored. From 1996-2003, he served as a member of the U.N. Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights and was the first U.S. citizen to chair a human rights body since Eleanor Roosevelt.

Excerpts from the in memoriam written by Kristi Rudelius-Palmer in the International Journal of Human Rights Education

Dr. Noah Bardach (1975–2025)

In Memoriam, UHRI

In memory of Dr. Noah Bardach, we share UHRI’s tribute from their Human Rights Day newsletter honoring Noah.

According to Noah, “the inception of UHRI sits at the convergence of three of my long standing interests: human rights, languages, and Nigeria.” He was looking up a Nigerian translation of the UDHR on the UN website, when he realized there was no way to listen to the translation. He thought of the millions of people around the world who cannot read, and recognized a serious void in human rights information that he could actually help address.

Noah and Hope Rieser Farley just happened to connect about this issue, and after chasing some connections and a meeting at the UN, they registered UHRI as a 501(c)3 nonprofit in 2016. Noah and Hope got to work, and Noah spent countless hours doing two of his favorite things: connecting with people around the world and leveraging technology to ensure that as many people as possible could access human rights information.

Noah’s and Hope’s partnership with the UN Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights (https://www.ohchr.org) led to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights audio app (UDHR.audio) which offers translations and recordings from all over the world to accompany the UN’s 570 written translations as well as new translations that had not yet been done.

Over the last decade, Noah’s effort, with the amazing support of UHRI interns, volunteers and collaborators, has reached people in 187 countries on every continent with recordings of the UDHR in 313 languages. In turn, the recordings have been shared hundreds of thousands of times. Noah’s goal was to have the UDHR recorded in all of its 500+ existing translations, but he soon encountered missing translations and others that needed revision. So he turned to that issue as well garnering volunteers and partners across the globe to help translate, review and record.

This past year, as he experienced the daily struggle of a terminal degeneragive disease, Noah achieved his most proudest accomplishment—linking this information to on the ground human rights organizations across the globe. Working closely with Malcolm Wright, one of our amazing facilitators and collaborators, he built in links to nearly 1000 human rights organizations across 187 countries so that anyone accessing our udhr.audio app could then choose to get more information, involved or even get help with issues they are facing.

Noah and Hope knew that it was important to take time to unpack all of the human rights information and connect it to our immediate lives. So we have an established Intergroup dialogue program to help communities unpack local human rights challenges and build bridges toward social justice. A summary and link to the latest dialogue series are below. Our trained team of facilitators are actively addressing the politically divisive world we living in, and invite us to uphold the very premise of human rights through the same values Noah held dear: dialogue, empathy, curiousity and action.

Learn more about Noah’s work at UHRI at uhri.ngo